Building on the platforms of others

If you follow me on Twitter then every so often you'll see a tweet crowing about some figure or other behind the Guardian Anywhere news-reading application we launched at FP. For instance, last month we distributed our 5 millionth copy of the Guardian.

The Guardian Anywhere has been available for well over 2 years now, and we've depended on the goodwill of the Guardian in allowing us to use their RSS feeds, their Open Platform and even some branding in our product. Even though they've launched their own official Android app, we haven't been quietly asked to remove ours - which is to their credit, given that there's no contract or other agreement covering this between Future Platforms and them.

Over the last few years there have been a few cases of third parties building on top of a platform, only for the platform provider themselves to launch a competing product or start restricting third-party provision of interfaces; Twitter is an obvious example.

There are compelling reasons for platform providers to do this, both commercial (keeping control of revenue opportunities) and customer-focused (ensuring that the end-user experience of your platform is one you're happy with). At FP we picked up a couple of projects for very large businesses that were unhappy with third parties owning the experience of their product, and wanted to do it themselves (OK, with our help).

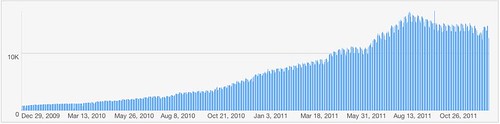

So I thought it might be interesting to show the impact of the Guardian launching their official Android product on the stats for the Guardian Anywhere. Here's a nice graph showing our sync traffic over the last couple of years (a sync being a device connecting in to download a copy of the newspaper; most users do this once a day):

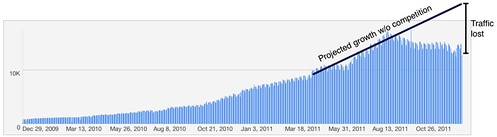

You can clearly see our traffic peak when the official product launched, but I'm surprised the subsequent decline wasn't greater. At the time I expected us to see the majority of our traffic drop off in a few months. Of course, it looks better than it is, because we would expect traffic to grow during this period. If you consider that (and take a mid-point projection of growth, at a rate somewhere between the huge take-up May-August 2010 and the average growth over the last 2 years), then it looks like so far we've lost somewhere between a half and a third of our traffic:

So it's slow decline, rather than immediate shut-down. I wonder if this is a familiar pattern to other folks who've found themselves competing with the platform they built atop?