Getting to grips with properties of sensors

One of the courses I'm really enjoying right now is Pervasive Computing. It involves playing with hardware (something I've never done to any real degree), ties into the trend of miniaturising or mobilising computing, and humours an interest I developed last year about the potential for mass use of sensors, and spoke about at Future of Mobile.

Dan Chalmers, who runs the Pervasive Computing course, has us playing with Phidgets in lab sessions, and very kindly lets us borrow some kit to play with at home, so I've had a little pile of devices wired up to my laptop for the last few days. The lab sessions are getting us used to some of the realities of working with sensors in the real world: notionally-identical sensors can behave differently, there are timing issues when dealing with them, and background noise is ever-present. At the same time we're also doing a lot of background reading, starting with the classic Mark Weiser paper from 1991 (which I'm now ashamed I hadn't already read), and moving through to a few discussing the role sensor networks can play in determining context (a topic I coincidentally wrote a hypothetical Google project proposal for as part of Business & Project Management, last term).

I've been doing a bit of extra homework, working on an exercise to implement morse code transmission across an LED and a light sensor: stick text in at one end, it's encoded into ITU Morse, flashed out by the LED, picked up by the light sensor, and readings translated back first into dots and dashes, then text. It's a nice playground for looking at some of those issues of noise and sensor variation, and neatly constrained: I can set up simple tests, have them fired from my laptop, and record and analyse the results quite simply.

Here's what the set-up looks like:

Note that the LED and light sensor are jammed as close together as I could get them (to try and minimise noise and maximise receipt of the signal). When I'm running the tests, I cover the whole thing to keep it dark. I have run some tests in the light too, but the lights in my home office aren't strong enough to provide a consistent light level, and I didn't want to be worrying about whether changes in observed behaviour were down to time of day or my code.

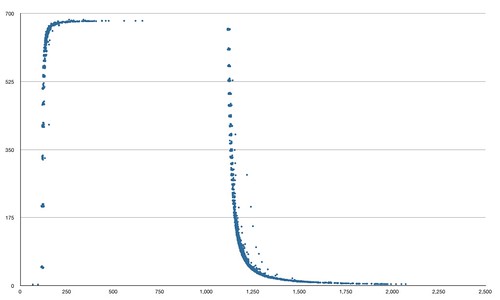

First thing to note is the behaviour of that LED when it's read by a light sensor. Here's a little plot of observed light level when you turn it on, run it for a second, then turn it off. I made this by kicking the light sensor off, having it record any changes in its readings, then turning the LED on, waiting a second, and turning it off. Repeat 200 times, as the sensor tends to only pick up a few changes in any given second. Sensor reading is on the Y axis, time on the X:

A few observations:

- This sensor should produce readings from 0 to 1000; the peak is around 680, even with an LED up against it. The lowest readings never quite hit zero;

- You can see a quick ramp-up time (which still takes 250ms to really get to full reading) and a much shallower curve when ramping down, as light fades out. Any attempt to determine whether the LED is lit or not needs to take this into account, and the speed of ramp-up and fade will affect the maximum speed that I can transmit data over this connection;

- There are a few nasty outlying readings, particularly during ramp-down: these might occasionally fool an observing sensor.

This is all very low-level stuff, and I'm enjoying learning about this side of sensors - but most of the work for this project has been implementing the software. I started out with a dummy transport which simulated the hardware in ideal circumstances: i.e. stick a dot or dash onto a queue and it comes off just fine. That gave me a good substrate on which to implement and test my Morse coding and decoding, and let me unit test the thing in ideal conditions before worrying about hardware.

The Phidgets API is really simple and straightforward: no problems there at all.

Once I got into the business of plugging in hardware, I had to write two classes which deal with real-world messiness of deciding if a given signal level means the bulb is lit or not. I used a dead simple approach for this: is it nearer the top or bottom of its range, and has it changed state recently? The other issue is timing: Morse relies on fixed timing widths of 1 dot between morse symbols, 3 between morse characters and 7 between words… but when it takes time to light and unlight a bulb, you can't rely on these timings. They're different enough that I could be slightly fuzzy ("a gap of 4 or fewer dots is an inter-character gap", etc.) and get decent results. There should be no possibility of these gaps being too short - but plenty of opportunity (thanks to delays in lighting, or signals travelling from my code to the bulb) for them to be a little slow.

I didn't implement any error checking or protocol to negotiate transmission speed or retransmits; this would be the next step, I think. I did implement some calibration, where the LED is lit and a sensor reading taken (repeat a few times to get an average for the "fully lit" reading).

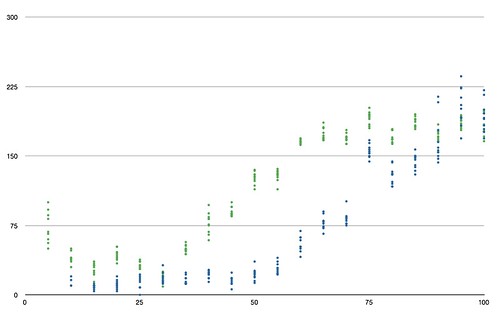

I ran lots of tests at various speeds (measured in words per minute, used to calculate the length in milliseconds of a dot), sending a sequence of pangrams out (to ensure I'm delivering a good alphabetic range) and measuring the accuracy of the received message by calculating its Levenshtein distance from the original text. Here's the results, with accuracy on the Y axis (lower is fewer errors and thus better) and WPM on the X:

You can see two sets of results here. The blue dots are with the sensor and LED touching; the green ones are with sensor and LED 1cm apart. You can see that even this small distance decreases accuracy, even with the calibration step between each test.

Strange how reliability is broadly the same until 50WPM (touching sensors) or 35WPM (1cm apart), then slowly (and linearly) gets worse, isn't it? Perhaps a property of those speed-ups/slow-downs for the bulb.

So, things I've learned:

- Unit testing wins, again; the encoding and decoding was all TDDd to death and I feel it's quite robust as a result. I also found JUnit to be a really handy way to fire off nondeterministic tests (like running text over the LED/sensor combo) which I wouldn't consider unit tests or, say, fail an automated build over;

- I rewrote the software once, after spending hours trying to nail a final bug and realising that my design was a bit shonky. My first design used a data structure of (time received, morse symbol) tuples. Second time around I just used morse symbols, but added "stop character" and "stop word" as additional tokens and left the handling of timing to the encoding and decoding layer. This separation made everything simpler to maintain. Could I have sat down and thought it through more first time around? I have a suspicion my second design was cleaner because of the experiences I'd had first time around;

- I'm simultaneously surprised at the speed I managed to achieve; there was always some error, but 50 WPM seemed to have a similar rate to lower speeds. The world record for human morse code is 72.5 WPM, and I'm pretty sure my implementation could be improved in speed and accuracy. For instance, it has no capacity to correct obviously wrong symbols or make best-guesses.

Things I still don't get:

- Why accuracy decreases when the sensors 1cm apart are run super-slowly. I suspect something relating to the timing and fuzziness with which I look for dot-length gaps;

- Why the decrease in accuracy seems linear after a certain point. I would instinctively expect it to decrease linearly as WPM increases.

And in future, I'd like to try somehow taking into account the shape of that lighting/dimming curve for the bulb - it feels like I ought to factor that into the algorithm for recognising state changes in the bulb. Also, some error correction or a retransmit protocol would increase accuracy significantly, or let me run faster and recover from occasional issues, giving greater throughput overall.

Update: I've stuck the source for all this on Github, here.