If it's walking like a duck, it should quack

I'll start by saying it: I don't understand what the fuss is about skeuomorphic interfaces. Or rather - I understand the fuss, but think it's misplaced. And there /is/ lots of fuss - it seems to be second only to Comic Sans in its notoriety in design circles just now. Witness Adam Greenfield ("somebody in Apple’s UX shop has saddled them with the most awful and mawkish and flat-out tacky visual cues"), or Clive Thompson in Wired ("skeuomorphs are hobbling innovation by lashing designers to metaphors of the past").

I've been collecting scattered thoughts and conversations about it for some time now. Hearing Jack Schulze defend it during a talk he co-presented with Timo Arnall at St. Bride's has spurred me into drawing this material together into a post.

Skeuomorphism is nothing new, as I learned during a chance conversation with Jo Rabin and Alex Craxton during post-MoMo pizza last year. Jo referenced the Doric columns of ancient Greece, which sported fluted shafts inherited from earlier wooden columns. In the originals, the flutes improved the strength of the structure and allowed for draining; once wood was abandoned these concerns were moot, but the form remained. Alex talked about Jugendstil, which used symbolic features on buildings that referred back to classical as well as natural form. And Alex G popped her head above the parapet just recently to comment that skeuomorphs remind her of paintings like those of the Flemish primitives, or even illusionism:

"either the artistic tradition in which artists create a work of art that appears to share the physical space with the viewer or more broadly the attempt to represent physical appearances precisely – also called mimesis"

Skeuomorphism is often rejected on the grounds of taste ("it looks tacky") or generates despondence from its shackling of digital interfaces to old metaphors. The latter offends for two reasons: the resulting interfaces are limited by their chains, and the approach is inherently backwards-looking. I can imagine similar views being expressed in architecture and art quite easily.

(In an attempt to depress still further, Jo also pointed out that we're seeing double-skeumorphs in some places: "the form of the iCal interface mimics a leatherette desk set - itself a skeuomorph of a proper leather bound one")

I think Adam's points are good ones, actually: as time goes on, it's clear that the digital metaphors we use for physical content become increasingly inappropriate. You can see the music and publishing industries struggling with this right now, as they try to sell easily-duplicated digital songs and books as though they were hard-to-copy physical items. The street finds its own uses for these metaphorical gaps.

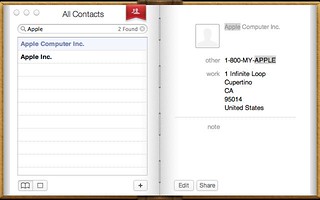

But even so I'm not convinced that skeumorphism is a bad thing. Watch Apple, the doyen of the design industry, take this approach in so many places that it can't be considered experimental or accidental: Newsstand, Find My Friends, Calendar, Address Book, probably others. Apple aren't perfect (cough Ping cough), but when they make such a deliberate and contentious choice across many products, I believe it's worth lending the approach some credence and trying to work out what they're up to.

At the BERG talk, Jack laid out a spirited defence which I completely buy: skeuomorphism is a justifiable and inevitable approach to take when the interactions in your interface are direct-manipulative and use physical metaphors. If they behave as though they are real things, should they not appear like real things? To paraphrase his point: if it's walking like a duck, it should quack.

I also find this line of reasoning supportive of my emotional response to skeuomorphs: on the desktop I find the hardback feel of the address book tacky; on a touch-screen device I find an almost-identical interface absolutely fine:

As Apple push computing beyond the creative industries who provided their early adopters and into the sweaty palms of the mass market, I think The S Word will become more appropriate. Pascal Raabe defends the approach in a recent article on the UsTwo blog, noting that "texture and physicality give clues as to how an interface works" (just look at the bevelling or brushed metal of modern UIs), as well as the pitfalls which arise when the expectations thus created are broken. It's easy to watch novice computing users and observe that they seem much more inclined to experiment, and make sensible first choices, when using iOS devices than when using desktop Macs or PCs. And as Marek pointed out in a chat after the BERG talk, end-users don't seem to find skeuomorphism as contentious as some of us working on software and interfaces.

Oh, and one thing I hope that critics and supporters of skeuomorphism can agree whole-heartedly on: as Matt pointed out, you don't half feel clever trotting that word out.

Update: Alex has posted some of her thoughts, explaining the illusionism side of things better than I have.