Getting to grips with properties of sensors

January 27, 2012 | CommentsOne of the courses I'm really enjoying right now is Pervasive Computing. It involves playing with hardware (something I've never done to any real degree), ties into the trend of miniaturising or mobilising computing, and humours an interest I developed last year about the potential for mass use of sensors, and spoke about at Future of Mobile.

Dan Chalmers, who runs the Pervasive Computing course, has us playing with Phidgets in lab sessions, and very kindly lets us borrow some kit to play with at home, so I've had a little pile of devices wired up to my laptop for the last few days. The lab sessions are getting us used to some of the realities of working with sensors in the real world: notionally-identical sensors can behave differently, there are timing issues when dealing with them, and background noise is ever-present. At the same time we're also doing a lot of background reading, starting with the classic Mark Weiser paper from 1991 (which I'm now ashamed I hadn't already read), and moving through to a few discussing the role sensor networks can play in determining context (a topic I coincidentally wrote a hypothetical Google project proposal for as part of Business & Project Management, last term).

I've been doing a bit of extra homework, working on an exercise to implement morse code transmission across an LED and a light sensor: stick text in at one end, it's encoded into ITU Morse, flashed out by the LED, picked up by the light sensor, and readings translated back first into dots and dashes, then text. It's a nice playground for looking at some of those issues of noise and sensor variation, and neatly constrained: I can set up simple tests, have them fired from my laptop, and record and analyse the results quite simply.

Here's what the set-up looks like:

Note that the LED and light sensor are jammed as close together as I could get them (to try and minimise noise and maximise receipt of the signal). When I'm running the tests, I cover the whole thing to keep it dark. I have run some tests in the light too, but the lights in my home office aren't strong enough to provide a consistent light level, and I didn't want to be worrying about whether changes in observed behaviour were down to time of day or my code.

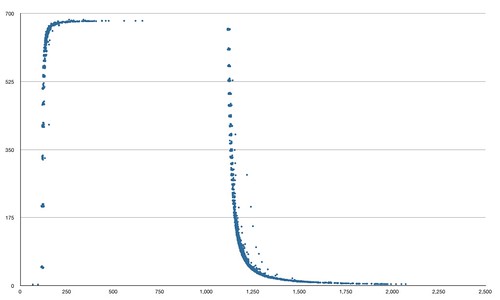

First thing to note is the behaviour of that LED when it's read by a light sensor. Here's a little plot of observed light level when you turn it on, run it for a second, then turn it off. I made this by kicking the light sensor off, having it record any changes in its readings, then turning the LED on, waiting a second, and turning it off. Repeat 200 times, as the sensor tends to only pick up a few changes in any given second. Sensor reading is on the Y axis, time on the X:

A few observations:

- This sensor should produce readings from 0 to 1000; the peak is around 680, even with an LED up against it. The lowest readings never quite hit zero;

- You can see a quick ramp-up time (which still takes 250ms to really get to full reading) and a much shallower curve when ramping down, as light fades out. Any attempt to determine whether the LED is lit or not needs to take this into account, and the speed of ramp-up and fade will affect the maximum speed that I can transmit data over this connection;

- There are a few nasty outlying readings, particularly during ramp-down: these might occasionally fool an observing sensor.

This is all very low-level stuff, and I'm enjoying learning about this side of sensors - but most of the work for this project has been implementing the software. I started out with a dummy transport which simulated the hardware in ideal circumstances: i.e. stick a dot or dash onto a queue and it comes off just fine. That gave me a good substrate on which to implement and test my Morse coding and decoding, and let me unit test the thing in ideal conditions before worrying about hardware.

The Phidgets API is really simple and straightforward: no problems there at all.

Once I got into the business of plugging in hardware, I had to write two classes which deal with real-world messiness of deciding if a given signal level means the bulb is lit or not. I used a dead simple approach for this: is it nearer the top or bottom of its range, and has it changed state recently? The other issue is timing: Morse relies on fixed timing widths of 1 dot between morse symbols, 3 between morse characters and 7 between words… but when it takes time to light and unlight a bulb, you can't rely on these timings. They're different enough that I could be slightly fuzzy ("a gap of 4 or fewer dots is an inter-character gap", etc.) and get decent results. There should be no possibility of these gaps being too short - but plenty of opportunity (thanks to delays in lighting, or signals travelling from my code to the bulb) for them to be a little slow.

I didn't implement any error checking or protocol to negotiate transmission speed or retransmits; this would be the next step, I think. I did implement some calibration, where the LED is lit and a sensor reading taken (repeat a few times to get an average for the "fully lit" reading).

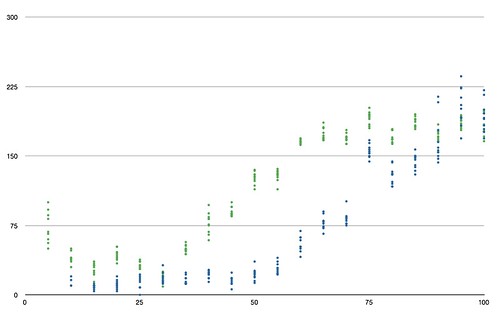

I ran lots of tests at various speeds (measured in words per minute, used to calculate the length in milliseconds of a dot), sending a sequence of pangrams out (to ensure I'm delivering a good alphabetic range) and measuring the accuracy of the received message by calculating its Levenshtein distance from the original text. Here's the results, with accuracy on the Y axis (lower is fewer errors and thus better) and WPM on the X:

You can see two sets of results here. The blue dots are with the sensor and LED touching; the green ones are with sensor and LED 1cm apart. You can see that even this small distance decreases accuracy, even with the calibration step between each test.

Strange how reliability is broadly the same until 50WPM (touching sensors) or 35WPM (1cm apart), then slowly (and linearly) gets worse, isn't it? Perhaps a property of those speed-ups/slow-downs for the bulb.

So, things I've learned:

- Unit testing wins, again; the encoding and decoding was all TDDd to death and I feel it's quite robust as a result. I also found JUnit to be a really handy way to fire off nondeterministic tests (like running text over the LED/sensor combo) which I wouldn't consider unit tests or, say, fail an automated build over;

- I rewrote the software once, after spending hours trying to nail a final bug and realising that my design was a bit shonky. My first design used a data structure of (time received, morse symbol) tuples. Second time around I just used morse symbols, but added "stop character" and "stop word" as additional tokens and left the handling of timing to the encoding and decoding layer. This separation made everything simpler to maintain. Could I have sat down and thought it through more first time around? I have a suspicion my second design was cleaner because of the experiences I'd had first time around;

- I'm simultaneously surprised at the speed I managed to achieve; there was always some error, but 50 WPM seemed to have a similar rate to lower speeds. The world record for human morse code is 72.5 WPM, and I'm pretty sure my implementation could be improved in speed and accuracy. For instance, it has no capacity to correct obviously wrong symbols or make best-guesses.

Things I still don't get:

- Why accuracy decreases when the sensors 1cm apart are run super-slowly. I suspect something relating to the timing and fuzziness with which I look for dot-length gaps;

- Why the decrease in accuracy seems linear after a certain point. I would instinctively expect it to decrease linearly as WPM increases.

And in future, I'd like to try somehow taking into account the shape of that lighting/dimming curve for the bulb - it feels like I ought to factor that into the algorithm for recognising state changes in the bulb. Also, some error correction or a retransmit protocol would increase accuracy significantly, or let me run faster and recover from occasional issues, giving greater throughput overall.

Update: I've stuck the source for all this on Github, here.

Second term

January 23, 2012 | CommentsSo I'm well into the second term of the Master's now. Last term was mostly things I'd done before: modules on Advanced Software Engineering, HCI and Business and Project Management (the last covering large-scale portfolio management: connecting projects back to overall strategy and issues relating to large organisations). A fourth module, Topics in Computer Science, exposed us to the pet topics of various lecturers: TCP congestion management, Scala, interaction nets, super-optimisation, networks, and more. I was pleasantly surprised by how current the syllabus is: we were using git, Android, EC2 and TDD during software engineering and the HCI course was very hands-on and practical. (On which topic: I have a write-up of my Alarm Clock project to go here soon).

This term is the exact opposite: pretty well everything is brand new. I'm taking modules in Adaptive Systems, Pervasive Computing, Limits of Computation, and Web Applications and Services - the latter being a rebranded Distributed Computing course, so we're knee-deep in RPC and RMI, with a promise of big-scale J2EE down the line. I'm also sitting in on, and trying to keep up with the labs for, Language Engineering.

Thus far it's Pervasive Computing and Language Engineering which are sitting at that sweet spot between "I think I can cope with this" and "this stuff is fun". They're both quite hands-on: for the former we're playing with Phidgets and learning about the practicalities of using sensors in the real world, something I've talked about recently but haven't done much with. Adaptive Systems is enjoyable, but quite deliberately vague - like Cybernetics, it's applicable in all sorts of situations but I'm finding it jelly-like, in the pinning-to-the-wall sense. Limits of Computation I have mentally prepared for a struggle with: it's mathematical, and maths is not my strong point (when taken beyond numeracy); and the Web Applications module is so far quite familiar, though I'm looking forward to getting my teeth into a project.

I can't emphasis how much fun this is. It's been years since I've been exposed to so much new stuff, and joining some of the dots between these areas is going to be interesting. That said I've still no idea what I'll be doing for my project in the third term; the idea of doing something Pervasive appeals strongly, but I'm waiting for inspiration to strike. If that doesn't happen I might return to superoptimisation and see if I can carve off a dissertation-sized chunk to look into, perhaps something around applying it to Java byte code…

Building on the platforms of others

January 11, 2012 | CommentsIf you follow me on Twitter then every so often you'll see a tweet crowing about some figure or other behind the Guardian Anywhere news-reading application we launched at FP. For instance, last month we distributed our 5 millionth copy of the Guardian.

The Guardian Anywhere has been available for well over 2 years now, and we've depended on the goodwill of the Guardian in allowing us to use their RSS feeds, their Open Platform and even some branding in our product. Even though they've launched their own official Android app, we haven't been quietly asked to remove ours - which is to their credit, given that there's no contract or other agreement covering this between Future Platforms and them.

Over the last few years there have been a few cases of third parties building on top of a platform, only for the platform provider themselves to launch a competing product or start restricting third-party provision of interfaces; Twitter is an obvious example.

There are compelling reasons for platform providers to do this, both commercial (keeping control of revenue opportunities) and customer-focused (ensuring that the end-user experience of your platform is one you're happy with). At FP we picked up a couple of projects for very large businesses that were unhappy with third parties owning the experience of their product, and wanted to do it themselves (OK, with our help).

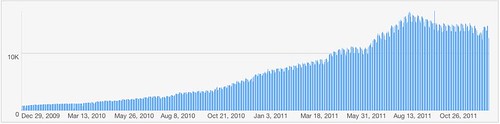

So I thought it might be interesting to show the impact of the Guardian launching their official Android product on the stats for the Guardian Anywhere. Here's a nice graph showing our sync traffic over the last couple of years (a sync being a device connecting in to download a copy of the newspaper; most users do this once a day):

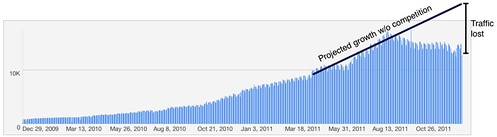

You can clearly see our traffic peak when the official product launched, but I'm surprised the subsequent decline wasn't greater. At the time I expected us to see the majority of our traffic drop off in a few months. Of course, it looks better than it is, because we would expect traffic to grow during this period. If you consider that (and take a mid-point projection of growth, at a rate somewhere between the huge take-up May-August 2010 and the average growth over the last 2 years), then it looks like so far we've lost somewhere between a half and a third of our traffic:

So it's slow decline, rather than immediate shut-down. I wonder if this is a familiar pattern to other folks who've found themselves competing with the platform they built atop?

Stroking, not poking

January 03, 2012 | CommentsA couple of weeks back, I started writing about a design project I'm doing as part of my MSc coursework. In the course of thinking about what makes mobile interfaces emotionally engaging, I came up with a half-baked theory that for evolutionary reasons long, languid gestures like strokes are more emotionally satisfying than the stabbing, poking motions we often use when, say, clicking buttons on touch-screens: "stroking, not poking".

I reached out to a few friends on Facebook to see if anyone could help me find some justification for this, and had a great response. A couple of publications stand out; firstly, from The Role of Gesture Types and Spatial Feedback in Haptic Communication by Rantala et al. (which Mat Helsby pointed me at):

"…support can be found for the view that interaction with haptic communication devices should resemble nonmediated interpersonal touch. Squeezing and stroking are closer to this ideal as the object of touch (i.e., the haptic device) can be understood to represent the other person and particularly his/her hand. To put it simply, stroking and squeezing the hand of another person are more common behaviours than moving (or shaking or pointing with)it."

and

"Preference for squeezing and stroking can be attributed to several reasons. Both methods were based on active touch interaction with the device whereas moving used an alternative approach of free-form gestures. Profound differences can be identified between these input types. Moving supported mainly a use strategy where one pointed or poked with the device, as studied by Heikkinen et al. Conversely, when squeezing and stroking, the device could be understood to be a metaphor of the recipient. This could have affected the participants’ subjective ratings as the metaphor strategy was closer to unmediated haptic communication. Furthermore, when rotating or shaking a passive object, kinaesthetic and proprioceptive information from limb movements is dominant. It could be argued that because stroking and squeezing an object stimulates one’s tactile senses (e.g., vibration caused by stroking with one’s fingertip), these two manipulation types were preferred also with active vibro-tactile feedback."

Mat also pointed me at The Handbook of Touch, which has a few choice quotes including this one:

"In addition to the decoded findings, extensive behavioural coding of the U.S. sample identified specific tactile behaviours associated with each of the emotions. For example, sympathy was associated with stroking and patting, anger was associated with hitting and squeezing, disgust was associated with a pushing motion…"

What Tom Did Next

December 31, 2011 | Comments So, here's another one of them end-of-year posts. 2011 was fun. Lots of fun: a couple of weeks travelling around Japan with Kate, furry tendencies indulged at Playgroup Festival, LoveBox and Sonar Festival followed by a few days lounging in Valencia all stand out.

So, here's another one of them end-of-year posts. 2011 was fun. Lots of fun: a couple of weeks travelling around Japan with Kate, furry tendencies indulged at Playgroup Festival, LoveBox and Sonar Festival followed by a few days lounging in Valencia all stand out.

Leisure-wise I did just about enough running (barely keeping a 100km/month average) but Not Enough Aikido (once a week with a trip to Edinburgh to see two old masters: Sugawara Shihan and Bryan Rieger). I slacked off a little when it came to writing, too, with just a Summer workshop with Wendy and a few trips to Flash Fiction favourite Not For The Faint Hearted. 6 or so weekends were merrily spent airsofting at UCAP Virus, before their incredible hospital site was shut for demolition in December. I also manage to get up to London to see quite a few talks this year: Sherry Turkle by herself and with Aleks Krotoski, a couple of School of Life events, Richard Dawkins presenting The Magic of Reality, Guy Kawasaki, and the incredible show that is War Horse. Oh, and Robin Dunbar came to Shoreham in February.

Work gave me a welcome excuse for travel once again: I spoke at Mobile World Congress in Barcelona, briefly at LIFT11, introduced Kirin at Mobile 2.0 Europe and had a lot of fun at UXCampEurope in Berlin and the Quantified Self event in Amsterdam. In the UK I blathered on at the Online Information Conference, Mobile Monday, UX Brighton, the Future of Mobile, Telco 2.0, and a BBC internal day for their UX & Design team. And I had an amazing weekend at OverTheAir in Bletchley Park, and got to attend a few of the expertly organised Rewired State Hack Days.

FP shipped a succession of products to be proud of this year: Davos Pulse for CNBC, the Radio 1 Big Weekend, Glastonbury Festival, AA Breakdown & Traffic, TheTicketApp and Hotels on WebOS for LastMinute.com, and the Viz Profanisaurus for Nokia devices, to name a few. Our Guardian Anywhere app for Android went past 100,000 installs and is about to shift its 5 millionth copy of the Guardian, and we open-sourced Kirin, our approach to blending web apps and native code. Just before Christmas I popped into FPHQ for a sneak peek of a few projects that'll ship early next year, and they're looking good.

And big changes in October, when I sold Future Platforms to Vexed Digital and started on a Master's at Sussex University, which I'm really enjoying. All of which brings me to what's next…

At the end of this year my involvement with FP is ending, beyond contributing to the Vexed newsletter for a little bit, and popping up in public on their behalf very occasionally. And whilst I'll be at Sussex until August/September working on my dissertation, I'm already starting to think about what I want to do next. It's going to be something like this:

- Products, not service: I've spent my whole career so far building software to order for other people. That's been great for giving me variety (I've launched over 250 products), but I'd like to be involved both before the decision to build is made, and after launch. So next time I want to be in a product company;

- Consumer-facing: I'm interested in making things for real people to use in their everyday lives. I get a little dopamine rush when I meet someone who's used things I helped ship;

- Mobile or internet: I've spent my life working in one or the other, and every day they get closer. I still find them both incredibly exciting places to be working: we've still a great deal of work to do in (un)wiring our species together;

- Working in a cross-disciplinary team: over the last 5 years I developed an interest in the overall process of Getting Stuff Launched, and I still enjoy the variety of working with a range of smart folks with different skills, backgrounds and languages: designers, developers, testers, marketers, biz dev people, whatever;

- Big jobs: Flirtomatic is probably the most-used product I've worked on, with 5 million users. I don't think it too many; in future I'd like to go bigger;

- Elsewhere; I've enviously watched a few friends heading towards StartupChile, and have a hankering to try being somewhere else for a bit.

I think 2012 is going to be fun :)