Making Sense of Sensors, Future of Mobile 2011

October 03, 2011 | CommentsI've been getting quietly interested in the sensors embedded in mobiles over the last few years, and Carsonified kindly gave me a chance to think out loud about it, in a talk at Future of Mobile a couple of weeks ago.

At dConstruct I noted that Bryan and Steph produce slides for their talks which work well when read (as opposed to presented), and I wanted to try and do the same; hopefully there's more of a narrative in my deck than in the past. And it goes something like this...

Our mental models of ourselves are brains-driving-bodies, and the way we've structured our mind-bicycles is a bit like this too: emphasis on the "brain" (processor and memory). But this is quite limiting, and as devices multiply in number and miniaturise, it's an increasingly unhelpful analogy: a modern mobile is physically and economically more sensor than CPU. And perhaps we're due for a shift in thinking along the lines of geo-to-heliocentrism, or gene selection theory, realising that the most important bit of personal computing isn't, as we've long thought, the brain-like processor in the middle, but rather the flailing little sensor-tentacles at the edges.

There's no shortage of sensors; when I ran a test app on my Samsung Galaxy S2, I was surprised to find not just acceleration, a magnetometer and orientation but light, proximity, a gyroscope, gravity, linear acceleration and a rotation vector sensor. There's also obviously microphone, touch screen, physical keys, GPS, and all the radio kit (which can measure signal strengths) - plus cameras of course. And in combination with internet access, there's second-order uses for some of these: a wi-fi SSID can be resolved to a physical location, say.

Maybe we need these extra senses in our devices. The bandwidth between finger and screen is starting to become a limiting factor in the communication between man and device - so to communicate more expressively, we need to look beyond poking a touch-screen. Voice is one way that a few people (Google thus far, Apple probably real soon) are looking - and voice recognition nowadays is tackled principally with vast datasets. Look around the academic literature and you'll find many MSc projects which hope to derive context from accelerometer measurements; many of them work reasonably well in the lab and fail in the real world, which leads me to wonder if there's a similar statistical approach that could be usefully taken here too.

But today, the operating system tends to use sensors really subtly, and in ways that seem a bit magical the first time you see them. I remember vividly turning my first iPhone around and around, watching the display rotate landscape-to-portrait and back again. Apps don't tend to be quite so magical; the original Google voice search was the best example I could think of of this kind of magic in a third-party app: hold the phone up to your ear, and it used accelerometer and proximity sensors to know it was there, and prompt you to say what you were looking for - beautiful.

Why aren't apps as magical as the operating system use of sensors? In the case of iPhone, a lot of the stuff you might want to use is tucked away in private APIs. There was a bit of a furore about that Google search app at the time, and the feature has since been withdrawn.

(In fact the different ways in which mobile platforms expose sensors are, Conway-like, a reflection of the organisations behind those platforms. iOS is a carefully curated Disneyland, beautifully put together but with no stepping outside the park gates. Android offers studly raw access to anything you like. And the web is still under discussion with a Generic Sensor API listed as "exploratory work", so veer off-piste to PhoneGap if you want to get much done in the meantime.

I dug around for a few examples of interesting stuff in this area: GymFu, Sonar Ruler, NoiseTube and Hills Are Evil; and I spoke to a few of the folks behind these projects. One message which came through loud-and-clear is that the processing required for all their applications could be done on-device. This surprised me, I expected some of this analysis to be done on a server somewhere.

Issues of real-world messiness also came up a few times: unlike a lab, the world is full of noise, and in a lab setting you would never pack your sensors so tightly together inside a single casing. GymFu found, for instance, that the case design of the second generation iPod touch fed vibrations from the speaker into the accelerometer. And NoiseTube noticed that smartphone audio recording is optimised for speech, which made it less adequate for general-purpose noise monitoring.

Components vary, too, as you can see in this video comparing the proximity sensor of the iPhone 3G and 4, which Apple had to apologise for. With operating systems designed to sit atop varying hardware from many manufacturers (i.e. Android), we can reasonably expect variance in hardware sensors to be much worse. Again, NoiseTube found that the HTC Desire HD was unsuitable for their app because it cut off sound at around 78dB - entirely reasonable for a device designed to transmit speech, not so good for their purposes.

And don't forget battery life: you can't escape this constraint in mobile, and most sensor-based applications will be storying, analysing or transmitting data after gathering it - all of which takes power.

I closed on a slight tangent, talking about a few places we can look for inspiration. I want to talk about these separately some time, but briefly they were:

I closed on a slight tangent, talking about a few places we can look for inspiration. I want to talk about these separately some time, but briefly they were:

- The Dark Materials trilogy of Philip Pullman, and daemons in particular. If these little animalistic manifestations of souls, simultaneously representing their owners whilst acting independently on their behalf, aren't good analogies for a mobile I don't know what is. And who hasn't experienced intercision when leaving their phone at home, eh…? Chatting to Mark Curtis about this a while back, he also reckoned that the Subtle Knife itself ("a tool that can create windows between worlds") is another analogy for mobile lurking in the trilogy;

- The work of artists who give us new ways to play with existing senses - and I'm thinking particularly of Animal Superpowers by Kenichi Okada and Chris Woebken, which I saw demonstrated a few years back and has stuck with me ever since;

- Artists who open up new senses. Timo Arnall and BERG. Light paintings. Nuff said.

It's not all happy-clappy-future-shiny of course. I worry about who stores or owns rights to my sensor data and what future analysis might show up. When we have telehaematologists diagnosing blood diseases from camera phone pictures, what will be done with the data gathered today? Most current projects like NoiseTube sidestep the issue by being voluntary, but I can imagine incredibly convenient services which would rely on its being gathered constantly.

So in summary: the mental models we have for computers don’t fit the devices we have today, which can reach much further out into the real world and do stuff - whether it be useful or frivolous. We need to think about our devices differently to really get all the possible applications, but a few people are starting to do this. Different platforms let you do this in different ways, and standardisation is rare - either in software or hardware. And there’s a pile of interesting practical and ethical problems just around the corner, waiting for us.

I need to thank many people who helped me with this presentation: in particular Trevor May, Dan Williams, Timo Arnall, Jof Arnold, Ellie D’Hondt, Usman Haque, Gabor Paller, Sterling Udell, Martyn Davies, Daniele Pietrobelli, Andy Piper and Jakub Czaplicki.

Open sourcing Kirin

September 30, 2011 | CommentsI've written a few times about the general dissatisfaction I (and the team at FP) have been feeling over HTML5 as a route for delivering great mobile apps across platforms.

Back in June, I did a short talk at Mobile 2.0 in Barcelona where I presented an approach we've evolved, after beating our heads against the wall with a few JavaScript toolkits. We found that if you're trying to do something that feels like a native app, HTML5 doesn't cut it; and we think that end-users appreciate the quality of interface that native apps deliver. We're not the only ones.

Our approach is a bit different: we take advantage of the fact that the web is a standard part of any smartphone OS, and we use the bit that works most consistently across all platforms: that is, the JavaScript engine. But instead of trying to build a fast, responsive user interface on top of a stack of browser, JavaScript, and JavaScript library, we implement the UI in native code and bridge out to JavaScript.

Back-end in JavaScript: front-end in native. We think this is the best of both worlds: code-sharing of logic across platforms whilst retaining all the bells and whistles. We've called the product which enables this Kirin.

Kirin isn't theory: after prototyping internally, we used it for the (as of last night) award-winning Glastonbury festival app (in the Android and Qt versions) and have established that it works on iOS too.

Now, we're a software services company; we aren't set up to sell and market a product, but we think Kirin might be useful for other people. So we've decided to open source it; and where better to do that than Over The Air, just after a talk from James Hugman (who architected Kirin and drove it internally).

You can find Kirin on GitHub here. Have a play, see what you think, and let us know how you get on.

Modding mobile apps

September 20, 2011 | CommentsdConstruct this year was a chance to see Bryan and Steph talk, and as usual I found their presentation fascinating and thought-provoking. One of their themes was to call for a "useful unfinished-ness" to products (slides 29-44):

"Issuing your customers with something that is rough, incomplete, and possibly even substandard seems counterintuitive but there is growing evidence that people don't necessarily want the perfect product, they prefer to deal with something ragged around the edges that they can adapt or improve."

- Loose, by Martin Thomas

This got me thinking as to how, in mobile, this useful unfinished-ness might be manifested; sidestepping the native/web debate briefly, how we could build mobile apps that allow themselves to be adapted or improved? I thought it'd be worth listing methods I can think of; can anyone think of more?

- Intents (Android only) - OpenIntents has a good list from third-party apps, Google publish a list for their apps;

- Downloadable SDKs, e.g. Facebook or OpenFeint;

- Custom URL schemes (Android and iOS), there are a couple of databases here and here, in combination with the canOpenURL call (on iOS) and I suspect some variant of isIntentAvailable on Android (tho I'm not 100% sure of the latter);

- Opening the source; not ideal as it'd likely mean third parties have to build a new copy of your app and distribute it; but it felt remiss to leave it off the list;

- Web services, so the data your app uses can be pulled in from a variety of sources;

- Push notifications or other messaging from outside your app (e.g. SMS), which your app can pick up on and react to;

Anyone think of any other sneaky waves of plugging mobile apps together?

How fast do users upgrade Android apps?

August 10, 2011 | CommentsAlex Craxton asked a question on Twitter, around how quickly users do or don't upgrade their applications. Quick as a flash, Mr Hugman had dug out the relevant graphs from our analytics of The Guardian Anywhere. The following two graphs show the transition between two minor versions of the product - from 2.15 to 2.17 (2.16 was a very short-lived version we rolled out a bug fix for):

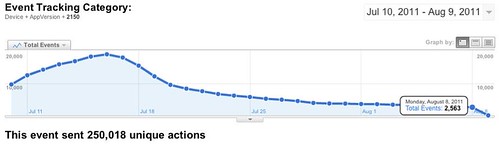

Ramp-down from 2.15:

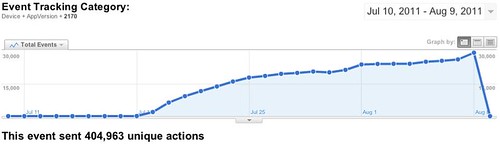

Ramp-up from 2.17:

They're plotting the number of synchronisations we've had from each version, per day. We typically see one sync per active user per day.

The Guardian Anywhere currently has 36,440 users with active installations; given that by the 8th August we had 29,745 syncs from version 2.17, this equates to 81% of our audience upgrading to the latest version within 5 weeks of launch. Hope that helps, Alex!

Diary.com, HTML5: Give Me My Pony!

July 22, 2011 | CommentsTechCrunch have been running a story about Diary.com adopting HTML5 for their mobile efforts. I found it quite a strange article, and it plays to some of the scepticism I've been experiencing recently around HTML5 as a nirvana for cross-platform app development.

To me, the article reads like a sequence of arguments against taking such an approach:

- Performance problems: "The performance of the Diary Mobile App… was the biggest challenge", "it wasn’t easy, performance was a huge issue at times it took days to figure out, and simple things like too much logging and poorly constructed ‘for’ loops actually made our app unusable during our journey."

- Reliance on third-party toolkits which are outside your control: "Sencha Touch is quite a beast and we’ve had to patch quite a lot of it to make it more performant and apply bugfixes", "we had some serious issues with the performance of Sencha Touch on some of the input fields that we had to provide fixes for"

- They ended up having to do native development anyway: "We built two Phonegap plugins; a Flurry API PhoneGap plugin for iOS (to be released open source in the future, and another to use the Local Notifications on iOS (also open source plans)"

- …and it sounds like they had to build a new API to service the back-end of the app (which admittedly they can probably reuse elsewhere): "We built an entirely REST API for which the app communicates with to make it as efficient and fast as possible"

This doesn't sound like an easy route out of the pain of cross-platform native development to me. Hats off to the Diary.com team who've made this work - HTML5 clearly hasn't provided a simple solution to their problems. And from a quick look at the reviews on the Android marketplace, end-users are reporting sluggishness in the app (something we've noted they really care about) and the lack of a native look-and-feel (see screenshot, right).

This doesn't sound like an easy route out of the pain of cross-platform native development to me. Hats off to the Diary.com team who've made this work - HTML5 clearly hasn't provided a simple solution to their problems. And from a quick look at the reviews on the Android marketplace, end-users are reporting sluggishness in the app (something we've noted they really care about) and the lack of a native look-and-feel (see screenshot, right).

I don't mean any disrespect to the diary.com team by pointing this out - they've clearly done a great deal of hard work in getting this product out there, and put a lot of effort into working around the limitations of HTML5 as far as they could, but despite this effort these limitations are still noticeable. And it's not just diary.com who seem to have experienced this - the FT, who've blazed a trail with their web apps for iOS, haven't launched a web product on Android yet: which doesn't suggest there's a great cross-platform story here.

How much of the current enthusiasm for HTML5-on-mobile is driven by wishful thinking on the part of the industry? It doesn't seem to offer much to end-users, who are often the ones funding the content with their wallets or eyeballs, and who are increasingly choosing to access mobile content through apps, not the web.

I can't help but think back to all those companies offering "write once, port automatically" solutions for J2ME a few years back. I've yet to see one which demonstrated that it could do the job well beyond a certain, simple class of applications, and I'm starting to feel the same way about HTML5 for mobile. In particular I think the cost of porting is being underestimated (just as it was for J2ME) - web-on-iOS might be performant, but getting it going beyond Apple kit takes time and effort. To be fair to the diary.com team, the reviews I can see on the iTunes App Store are broadly positive - suggesting that on Apple devices HTML5 is a stronger contender, but weakening its case cross-platform.

I really really really want a pony, but that doesn't make it right for me to saddle up Mr Falletti and ride him around the office. And the fact that we want or need an easy way to do cross-platform apps doesn't mean the web will give us one. I'm leaning towards the same view I had with J2ME: you'll need a mix of techniques, tools and experience to do this well, you can't avoid dealing with the underlying platforms, and silver bullets are in short supply.

Thanks to James Hugman for his contributions to this post.